Calculator Interpreter

2017-07-09

I made a toy calculator language, interpreted it in Python, and made a REPL to interact with it!

So far, the language I made can:

- evaluate expressions (with add, subtract, and multiply operators)

- assign variables

- access previously assigned variables and use them in expressions

Making this was a lot of fun. Before I started, it seemed like too intimidating a project. I am really glad I went for it anyway, and appreciate the encouragement I got from other people to start it. (a special thanks to Elias!)

I feel it helped me to understand how programming languages work a little better, and made me even more intrigued to learn more. Working on this also demystified what interpreters and compilers are; including on an intuitive level: there is no black box inside the computer that turns the code I write into meaning; there are just lots of layers of code that do different parts of the task.

I decided to do a write up of this project in a way that would have helped me if I'd found it when I started this project.

What does the language look like?

When I made up the language, I tried to make it interesting - I thought that would be more fun. Since then I have spent sometime debugging only to realize the script was working - I'd made a mistake with my own interesting syntax (I've also learnt to appreciate error messages more, after spending time with my own badly written ones).

I found out that it's important to have a written grammar for the language. This helps when you are trying to remember interesting syntax rules, and also maps the way you parse the language later. It should include terminal symbols, non terminal symbols, and rules.

There is only one rule in my language: all statements must be wrapped in | and >, which are equivalent to "(" and ")".

Terminal symbols are units that cannot really be broken down further. They are:

!ADD : + operator

!SUB : - operator

!MUL : x operator

-> : assignment symbol

integers 0-9

names ?[^ ]+ : variable names must start with `?`, for example `?x`

| : open bracket

> : close bracket

There are four non terminal units in the language. Non terminals are made of terminal symbols. They are:

PROGRAM := STATEMENT +

STATEMENT := EXPRESSION

ASSIGNMENT

EXPRESSION := | EXPRESSION operator EXPRESSION >

| INTEGER >

| NAME >

ASSIGNMENT := | NAME <- EXPRESSION >

This means that there are four structures of meaning in the language. Each full piece of code is a program. Each program is made of one or more statements. A statement can be an expression or an assignment.

An expression can be either:

- two expressions separated by an operator (for example

| 2 !ADD 3 >or| 4 !ADD ?y >) - a number (for example

| 5 >) - a name or variable (for example

| ?x >)

An assignment has the name on the left, an arrow (<-) to show assignment, followed by an expression (for example | ?x <- | 4 > > )

The following statements are grammatically correct:

| 5 !MUL 7 >| | 2 !ADD | 3 !ADD 1 > > !SUB | 5 !ADD 7 > >| ?x <- | 1 > >| ?x <- | 5 !ADD 7 > > | 20 !ADD 10 >

What is an interpreter?

An interpreter takes a program and input and executes it:

P + x ---> P(x)

For more about the difference between interpreters and compilers read this link

An interpreter has these stages:

- lexer (split the input into tokens)

- parser (parse the tokens to get an abstract representation of the program)

- semantic analysis (add meaning to the representation)

- evaluation

My interpreter does step three and four in one step.

Part 1: get the tokens (lexer)

Programs or scripts are just text. The text can be broken up into 'tokens' which have meaning, like words in natural languages. This involves separating the tokens, and figuring out what kind of token each is. This step is called lexical analysis.

To check what kind of token each is, regular expressions are used to look for patterns. In my language this is quite straight forward. For example, all variable names start with ? so I can find out if something is a variable by checking if it matches this regular expression: r'\?.+?', and then assign the correct token type tag.

At the end of this stage there is a series of tokens, stored as named tuples that have both the value and the type.

What is a recursive descent parser?

My interpreter uses the recursive descent parser model. This kind of parser parses input according to the grammar of the language: it has a set of procedures (ie. functions), and each function deals with a separate non terminal unit of the grammar. These procedures call each other recursively. So for my language the non terminal units are: program, statement, expression, assignment; parse_program calls parse_statement, which calls parse_assignment or parse_expression. You can have an expression inside an expression inside an expression, so parse_expression might have to call itself several times.

The type of recursive descent parser I wrote, called predictive, only looks at most a few tokens ahead at a time. So it looks ahead only enough to determine whether to send the input on to another function (and determine which function to send it to), or to return it.

Part 2: parse the tokens and make a representation of the code (parser)

This step takes a list of tokens, and according to their types it creates an abstract representation of the program.

The grammar of the language is used to organize the abstract representation of the program's meaning. My language's grammar has four non terminal parts:

- program

- statement

- expression

- assignment

Each of these four has a function to parse it; program, expression, and assignment are represented by instances of class objects. Statements are an attribute of the program:

class Program():

def __init__(self):

self.statements = []

class Expression():

def __init__(self, left=None, right=None, operator=None, value=None):

self.left = left

self.right = right

self.operator = operator

self.value = value

self.expression = True

class Assignment():

def __init__(self, name=None, value=None):

self.name = name

self.value = value

self.expression = False

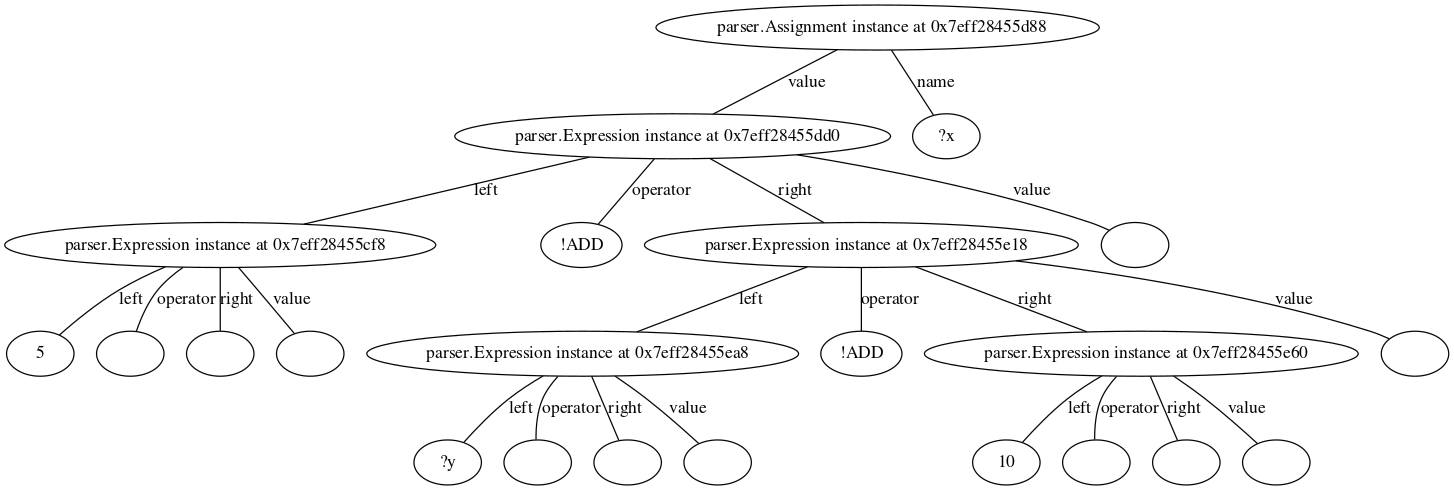

The following script:

| ?x <- | 5 !ADD | ?y !ADD 10 > > >

Could be represented by:

How is this model created? The parser has a set of functions to parse the four different units of the grammar. The functions call each other recursively and consume the tokens.

For example, when parse_program is called it checks there are tokens, and then calls parse_statement in a while loop until there are no more tokens. parse_statement looks at the next few tokens to determine whether the statement is an expression or assignment. If there is a variable name (starting with ?) and an assignment symbol (<-) it calls parse_assignment, otherwise it calls parse_expression.

At the end of this stage there is an instance of the Program class, which has a list of statements as an attribute. Each statement can be an instance of either the Expression class or the Assignment class, and can contain another instance of the expression class as an attribute. The expression instances do not yet have value attributes, these will be added in the evaluation stage. We can call this an abstract syntax tree.

Part 3: semantic analysis and evaluation

This step iterates through the statements in the program, and determines their values. It is similar to step two, in that each non terminal part of the language grammar has an evaluate function, and the functions are called recursively to return the values of all levels of nested expressions.

At this point variables are also added to the dictionary; if a statement is an assignment instance, its name and value is added to the dictionary.

How does the REPL work?

REPL stands for read evaluate print loop. I made a REPL by writing a script that accepts input, evaluates it (interprets it according to the steps above), and prints the output, in a loop.

When you run the REPL script, it creates a dictionary and then enters a loop. Each cycle through the loop waits for input. If the input is 'q' the function returns and the program ends, if it's 'h' help is printed to the terminal.

Otherwise the interpret function is called on the input (the interpret function calls the lexer, parser, and evaluator), which returns the output. This part is inside of a try statement, so that if the input cannot be interpreted the REPL does not exit. The dictionary is also passed and returned, so that variables can be added to the dictionary.